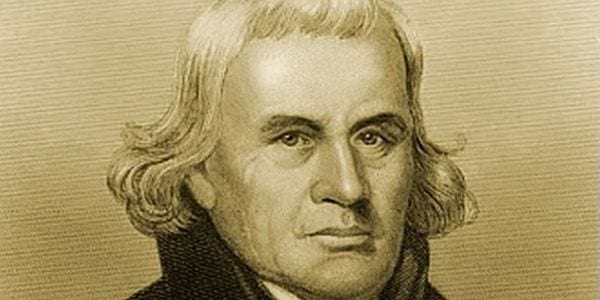

Francis Asbury, (1745–1816). One of the two first Methodist bishops in America. Sent to America by J. Wesley in 1771, he was very soon given supervision of all Methodist work in the country.

Some might call him a workaholic. Or maybe just utterly dedicated.

He certainly had the numbers: during his 45-year ministry in America, he traveled on horseback or in carriage an estimated 300,000 miles, delivering some 16,500 sermons.

He was so well-known in America that letters addressed to “Bishop Asbury, United States of America” were delivered to him. He crossed the Allegheny Mountains more than sixty times; he saw more of the American countryside than any other person of his generation; and he may have been the best–known man in North America.

Brief Historical Sketch of Francis’ Life

Francis Asbury was English born; born in Handsworth, Staffordshire, four miles from Birmingham (England) of poor parents who had been among the early converts of Methodism’s founder, John Wesley.

He dropped out of school before he was 12 to work as a blacksmith’s apprentice. By the time he was 14, he had been “awakened” in the Christian faith. He and his mother attended Methodist meetings, where soon he began to preach;

He began lay preaching when only sixteen and was apprenticed as a blacksmith. He was appointed a full-time Methodist preacher by the time he was 21.

In October 1771, Asbury landed in Philadelphia, there were only 600 Methodists in America. Within days, he hit the road preaching but pushed himself so hard that he fell ill that winter.

This was the beginning of a pattern: over the next 45 years, he suffered from colds, coughs, fevers, severe headaches, ulcers, and eventually chronic rheumatism, which forced him off his horse and into a carriage. Yet he continued to preach.

The Faithful Endurance and Organizational Leadership Skills Excelled Beyond All

Organization was Asbury’s gift.

He created “districts” of churches, each of which would be served by circuit riders—preachers who traveled from church to church to preach and minister, especially in rural areas. In the late 1700s, 95 percent of Americans lived in places with fewer than 2,500 inhabitants, and thus most did not have access to church or clergy. This is one reason Asbury pushed for missionary expansion into the Tennessee and Kentucky frontier—even though his and other preachers’ lives were constantly threatened by illness and Indian attacks.

Though a school dropout, Asbury launched five schools. He also promoted “Sunday schools,” in which children were taught reading, writing, and arithmetic.

Asbury pushed himself to the end. After preaching what was to be his last sermon, he was so weak he had to be carried to his carriage.

By then, though, Methodism had grown under his leadership to 200,000 strong. His legacy continued with the 4,000 Methodist preachers he had ordained: by the Civil War, American Methodists numbered 1.5 million.

When Asbury came to America in 1771 there were four ministers and about three hundred Methodists. When he began his work, Methodists were found only on the Atlantic seaboard.

At the close of his career, the movement had spread into every state as far as the Mississippi River, then the nation’s western boundary.